William III, Prince of Orange, alongside his wife Mary II, became one of England’s most intriguing rulers, sharing the throne in an unprecedented joint monarchy. From his early challenges under the Act of Seclusion to his marriage with Mary, their reign marked a turning point in British history. Explore how William’s leadership in the Glorious Revolution, his deep ties to Protestant Europe, and his unique partnership with Mary II helped shape the modern British monarchy. Read on to uncover the story of their reign, their personal journey from a reluctant marriage to a powerful alliance, and their lasting legacy.

Who Was William III?

William III and II, Prince of Orange, ruled England with his wife Mary II, making them the only joint sovereigns in English history. Their reign, during a time of great political change, helped shape a new era for the British monarchy. Born into the House of Orange-Nassau, William carried the title of Prince of Orange from birth, a position that made him influential in the Dutch Republic.

William held multiple titles across Europe. In the Dutch Republic, he served as Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Gelderland, and Overijssel starting in 1672. He remained in this role, similar to head of state, until he died in 1702. He was known as William II in Scotland, and in England and Ireland, he was crowned William III. He ascended to the English throne in 1689 after the Glorious Revolution, beginning his joint reign with Mary II. Mary passed away in 1694, but William continued to rule alone until his death in 1702, totalling 13 years on the British throne.

William was not only unique for his joint monarchy but also for his role in European politics. He fiercely defended Protestantism against Catholic powers like France. His various titles and roles underscored his broad influence, spanning multiple countries and shaping the political landscape of Europe during a critical period.

Table of Contents

- Early Life and Family

- Marriage to Mary II: A Political Alliance

- Joint Monarchy: William and Mary’s Reign

- Later Years and Legacy

Early Life and Family

William III was born on 4 November 1650 at Binnenhof in The Hague, just days after his father, William II, Prince of Orange, died. His father was a prominent figure in the House of Orange-Nassau, a family with significant political influence in the Dutch Republic. His mother, Mary, Princess Royal, was the eldest daughter of King Charles I of England, making William a grandson of an English monarch. This dual heritage connected William to both the Dutch Republic and the English throne, setting the stage for his future in European politics.

Orphaned shortly after birth, William was raised by his grandmother, Amalia of Solms-Braunfels, and educated by a series of tutors who prepared him for leadership. His upbringing focused on Protestant faith and his family’s political ambitions. Despite losing his father early, William’s royal lineage and the ongoing religious tensions ensured his importance in European affairs. His background paved the way for his leadership in the Glorious Revolution and his rise to the English throne.

Struggles and the Act of Seclusion

William’s early life was marked by his family’s Protestant faith, which later shaped his political and military career. His father, William II, supported the Protestant cause and sought to strengthen his power within the Dutch Republic. However, after his father’s death, the Dutch States General introduced the Act of Seclusion, barring William and his descendants from the office of Stadtholder to reduce the House of Orange’s influence.

Despite this setback, William’s royal lineage and the religious divide in Europe maintained his status as a Protestant leader from a young age. Raised under the guidance of his mother and grandmother, William was expected to reclaim his family’s traditional roles. This upbringing instilled a strong sense of duty and resilience in him. The Act of Seclusion presented significant challenges, but William’s bloodline and his father’s Protestant legacy destined him for leadership.

Stadtholdership and Political Ascent

William’s early political career faced challenges from the Act of Seclusion in 1654, which barred his family from holding the office of Stadtholder. This act, orchestrated by Dutch leader Johan de Witt and England’s Oliver Cromwell, aimed to limit the House of Orange’s power and promote a republican government.

However, in 1672, the Dutch Republic faced invasions from France, England, and allied forces. Amidst this crisis, public support for the House of Orange surged. At 21, William was appointed Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Gelderland, and Overijssel, despite the Act of Seclusion.

As Stadtholder, William quickly proved his leadership. He reorganised Dutch forces and forged key alliances against French expansion under Louis XIV. His efforts not only restored the House of Orange’s prestige but also solidified his status as a key Protestant leader in Europe. This success foreshadowed his later achievements in the Glorious Revolution and his rule over England.

Marriage to Mary II: A Political Alliance

In 1677, William married his cousin Mary II, the daughter of James, Duke of York, and second in line to the English throne. Their union was a politically motivated alliance, intended to bolster Protestant ties and counter Catholic influence in Europe. However, the marriage began on a difficult note. At just 15, Mary was unhappy with the arrangement. She had hoped for a romantic match and was devastated to learn she would marry her cousin, who was 12 years older. William, reserved and politically focused, did not meet her expectations. Adding to her distress, Mary, standing at 5 feet 11 inches, towered over William by nearly five inches—a detail that drew public scrutiny.

Wedding Day and Relationship

Their wedding day reflected their initial discomfort. Mary wept throughout the ceremony, overwhelmed by the union she had not chosen, while William remained stoic. Their families also had mixed reactions; Mary’s father, James, Duke of York, disapproved due to William’s Protestantism, which clashed with his Catholic beliefs. Meanwhile, King Charles II, Mary’s uncle, made jokes about the match, and the French court, led by Louis XIV, disapproved of another Protestant alliance in the English royal family.

After their marriage, Mary moved to the Netherlands. William, aware of the difficulties her mother—another Mary Stuart—faced in the Netherlands, worried she might also struggle. However, Mary quickly charmed the Dutch court and people with her warm personality. Her genuine interest in Dutch customs and her gracious nature won over the public, and she embraced her role as Princess of Orange. Over time, Mary grew to love the Netherlands, so much so that she hesitated to return to England even when duty called.

Despite their rocky start, William and Mary developed a deep bond of love and friendship. William, initially focused on the political benefits of their marriage, grew to admire Mary’s intelligence and strength. Mary, in turn, appreciated William’s dedication to her and their shared Protestant cause. Their mutual respect and affection flourished, transforming their marriage from a reluctant alliance into a partnership based on loyalty and love. This deep bond prepared them for their roles as England’s first and only joint sovereigns.

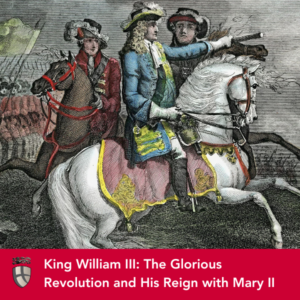

The Glorious Revolution and English Invasion

England’s political landscape was in turmoil when Parliamentarians approached William and Mary to oppose King James II. As a Catholic, James’s policies conflicted with Protestant England. In 1688, William led an invasion of England, which prompted James to flee, resulting in the Glorious Revolution. William’s invasion was nearly bloodless; James lost support and was declared to have abdicated.

Joint Monarchy: William and Mary’s Reign

After their successful invasion, William and Mary were crowned joint sovereigns in 1689, an unprecedented event in British history. Unlike previous queens who served as consorts, Mary was a reigning queen with equal authority to William. William originally planned for Mary to be the sole ruler, preferring not to take the throne by conquest. He wanted Mary, the rightful heir as James II’s daughter, to be queen. However, Mary insisted on ruling alongside William. Thanks to his own royal lineage as King Charles I’s grandson, William was able to share the throne with Mary, creating an unprecedented joint monarchy.

Their reign marked the beginning of a constitutional monarchy in Britain, significantly altering the balance of power between the monarchy and Parliament. During their coronation, William and Mary swore to govern according to Parliament’s rules, rather than uphold traditional royal laws. This oath was a clear break from past monarchs, who often claimed divine rights above Parliament’s laws. This shift set the stage for a new era in British politics, where the monarchy worked in cooperation with Parliament.

Mary II: Queen Regnant

Mary proved herself a capable and independent ruler, especially when William was away on military campaigns. She often managed state affairs with wisdom and poise, earning her a reputation as a well-loved queen. Her leadership balanced firmness with compassion, showing she was fit to rule alongside William. Their partnership, both personal and political, defined their reign. While William focused on military and foreign affairs, Mary managed domestic governance, ensuring stability. Their combined strengths made their joint rule effective and harmonious. Their reign not only cemented their place in history but also set a precedent for a more balanced and constitutional monarchy that would influence future British governance.

Later Years and Legacy

Mary’s death from smallpox in 1694, at the age of 32, left William devastated. He never remarried, and he cherished her memory for the rest of his life, famously wearing her wedding ring on a black ribbon around his neck, transformed into a locket that held a strand of her hair. After her death, William continued to rule alone, facing ongoing challenges from Jacobite supporters of the deposed James II, including a failed attempt by James to reclaim the throne in 1690, which ended with his defeat at the Battle of the Boyne.

William III’s legacy is complex: he is remembered as a champion of Protestantism, a military leader, and a king who played a crucial role in shaping the modern British monarchy. His reign, alongside Mary II, set the foundation for a constitutional monarchy that continues to influence today’s British political system.